Two decades ago, when SACD and DVD-Audio were recently introduced media options, TAS published an occasional, evolving list titled “Best in New Format Software.” The idea was that those taking the multichannel plunge could get ideas about where to start, in terms of music. Finding classical albums wasn’t hard, as the goal of those mixes was to create a recording representative of what the performance sounded like to an audience member located in a good seat in a specific venue. There were loads of those—from Telarc, Channel Classics, Pentatone, and many other labels.

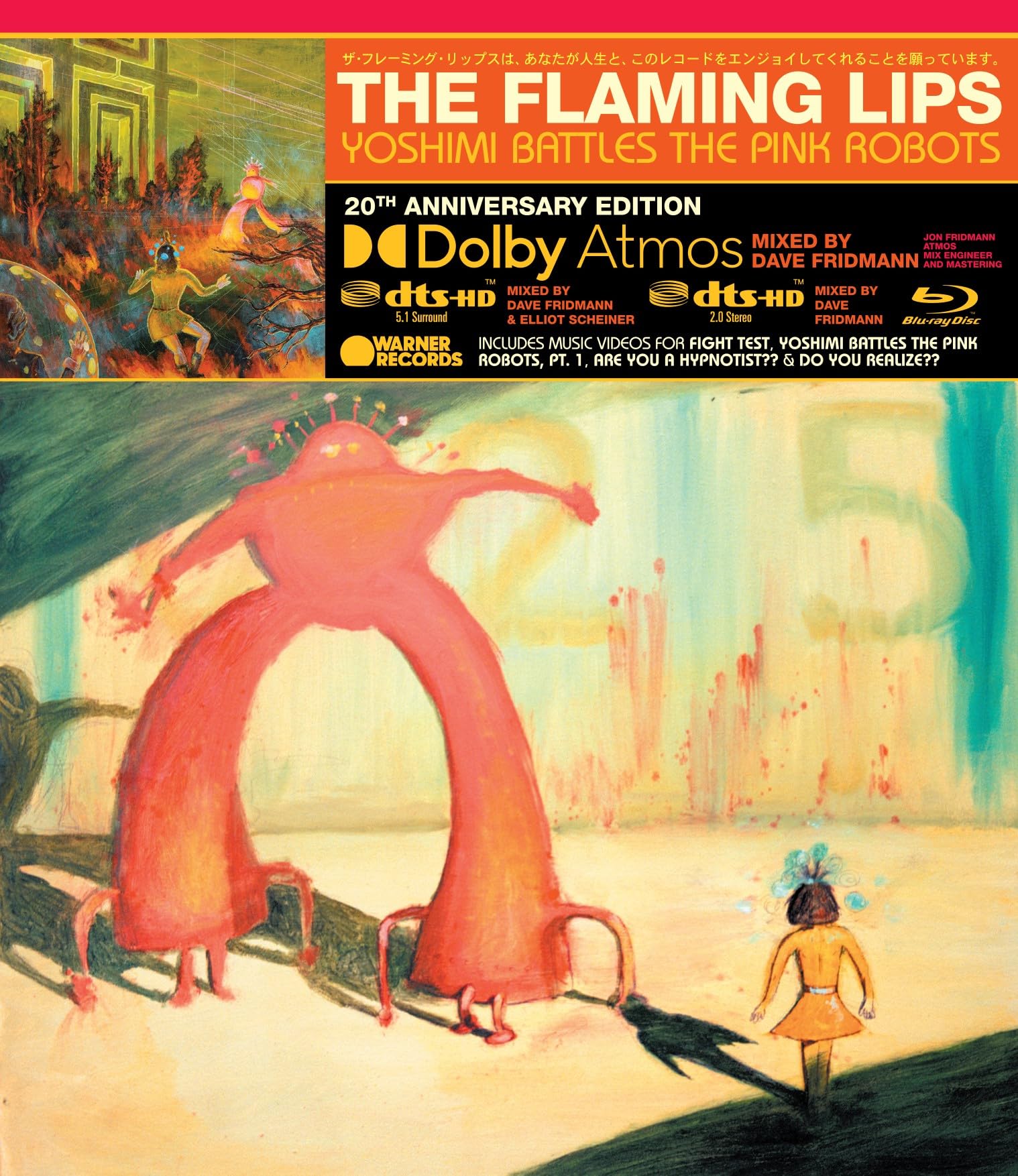

Finding non-classical content was more difficult. There were some older albums that seemed to have been waiting decades for a resurgence of interest in “surround sound” and worked well—Roxy Music’s Avalon or Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon, for example. But most were of the let’s-put-the-maracas-and-background-vocals-in-the-surround-channels variety—pleasant at best, distracting and gimmicky at worst. There were a few successful newer non-classical titles on SACD and DVD-A; two that come to mind are Beck’s Sea Change and Nickel Creek’s This Side. But one recording, issued in 2003 as a DVD-Audio disc, stood head-and-shoulders above everything else, and that was Yoshimi Battles the Pink Robots, the tenth studio album from the American rock band, the Flaming Lips.

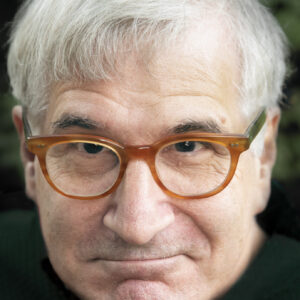

Trained in music production at SUNY Fredonia, Dave Fridmann was a founding member of the band Mercury Rev, winding down as their touring bassist in the early 1990s to develop his career as a go-to producer for musicians playing in various styles, with an emphasis on those characterized under the rubric of “indie rock.” In 1997, Fridmann and several partners built the Tarbox Road Studios in the small village of Cassadaga in western New York State. There, Fridmann has served in various engineering and production roles for scores of artists, including such high-profile groups as Weezer, Spoon, and Vampire Weekend. But he’s best known for his work with the Flaming Lips, having coproduced most of their albums for over 30 years. Fridmann won a Grammy for Best Engineered Album, Non-Classical in 2007 for the Flaming Lips’ At War With The Mystics.

Yoshimi Battles the Pink Robots, originally released in 2002, has been the Lips’ biggest commercial success to date, with over 850,000 copies sold. The album has a loose narrative structure, at least for its first half. The hero, a municipal employee named Yoshimi, goes up against an army of “evil robots” as themes of man vs. machine, pacifism, and the capacity for a product of technology to experience human emotion are explored, topics that resonate with current concerns about the growing importance of artificial intelligence in our society. The Yoshimi of the album title is a character inspired by Yoshimi P-We, a Japanese musician greatly admired by Flaming Lips frontman Wayne Coyne; she supplies some vocalizations heard on the album. Between P-We’s involvement, the sci-fi storyline, and the artwork, there’s an anime sensibility that’s mirrored in music possessing a deceptive simplicity but also currents of turbulent uncertainly running just below the surface.

The band at the time only consisted of three musicians—lead singer/guitarist Coyne plus multi-instrumentalists Michael Ivins and Steven Drozd. But the list of personnel for Yoshimi is misleading, as Wayne Coyne has said that his “instrument” is “the recording studio” and his role in developing the sonic character of each Flaming Lips album is substantial. The sound field is densely populated with sound effects, synthesizer blats and wheezes, electronically altered vocals, shards of instrumental commentary, wandering drums, and much more in a dizzying dreamscape that a listener may experience a bit differently with each repetition. Given its complexity, the album is surprisingly cogent in its original two-channel form—Dave Fridmann has been referred to as “the Phil Spector of the Alt-Rock Era” for the forward, dimensionally expansive presentation he achieves. Still, 2003’s 5.1 mix accommodates the music’s complexities far better, making use of the rear channels in a kinetic fashion that’s highly engaging.

For several years, Turbox Road has had the capacity to create Atmos mixes that Dave Fridmann and his son Jon, a recording professional with Atmos engineering and mastering expertise of his own, have utilized for artists including Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds, Vampire Weekend, and Carly Rae Jepsen. To mark the occasion of Yoshimi’s 20th anniversary, the Fridmanns worked with Wayne Coyne to create an immersive mix that further clarifies musical meaning beyond what the 5.1 mastering of 20 years ago accomplished, revealing additional strata of detail and expanding greatly the size of the soundstage perceived in even a modest-sized listening space. The height channels, in particular, add a degree of transparency and intelligibility that was hard to imagine when the album existed only in stereo.

The Blu-ray issued by Warner Records in partnership with Rhino holds the new Atmos mix as well as DTS-HD 5.1 and DTS-HD 2.0 versions of the program. Also included are five music videos and, in case your lava lamp is no longer working, an “animated visualizer” called “Bleep Blops” that you can watch on your computer monitor or television as the album plays. If that experience enhances your enjoyment of Yoshimi, you should probably decline a urine drug test at work for the next few days.

_______________

Ahead of the official release of the Warner/Rhino Blu-ray, WMG’s publicist arranged a Zoom meeting for me with the Fridmanns. I began by asking about Yoshimi’s path from stereo to Atmos—an undertaking that the elder Fridmann had been central to every step of the way.

Yoshimi Battles the Pink Robots was recorded between 2000 and 2002. The DVD-Audio and SACD formats were introduced in 1999. Was a surround version of the album something that was a consideration when the music was conceived and recorded?

Dave Fridmann: No. I certainly had an interest in that but our sole focus while creating the record was stereo.

So how did you and the band approach making the multichannel mix for the 2003 DVD-Audio release?

DF: Because I had an inherent interest in surround sound/theater sound, we had already accessed early 5.1 releases. The ones that really stood out to us were the Super Furry Animal’s Rings Around the World and Beck’s Sea Change. The ability to work with Elliot Scheiner, and the willingness of Warner Brothers to make that happen [was key.] I’ve been a huge fan of Elliot’s for a very long time—he mixed the Sea Change record. This was the guy we needed to do this with.

So Elliot participated in making the 5.1 version of Yoshimi?

DF: He was the primary mixer. Wayne and I went to Connecticut to work with him. We did recalls for all the songs and captured every input to my console digitally so that we had all the raw material, which is 80 tracks. We brought those with us to Elliot’s place and figured out how to approach the subject.

Did the development of the new immersive formats seem like an opportunity to elaborate on, or improve upon, what you’d done 20 years ago? Or was it more a matter of those earlier formats becoming extinct (DVD-Audio) or infrequently utilized (SACD)?

DF: Certainly, it was a great opportunity. I’d known about Atmos for a long time but within a day or two of Apple beginning to stream Atmos, the phone started ringing off the hook. “Send me the master. Send me the stems. Send me everything.” And I said, “OK, this is a real thing. We have to get ourselves set up and make sure we’re protecting all the artists we’ve worked with over the years, so we’re as prepared as we can be.” Immediately, I started listening in my home theater to Apple Music Atmos playback and, I’ll be frank, was disappointed with what I heard. We knew there were too many ways to make a bad Atmos mix and needed to make sure we were making good ones. But we thought it was a great opportunity to take advantage of, and because DVD-Audio and SACD had died and new playback devices weren’t being made for those formats, we thought, “This will be awesome. We get to reintroduce the surround sound version of what we did and go another step further.”

Jon Fridmann: I want to add that there was a long history of spatial-based audio projects by the Flaming Lips before the Yoshimi surround, like Zaireeka and Wayne’s parking lot experiments. There have always been rumblings about whether it was inspired by certain gaming experiences and how to continue, whether it was a VR or spatial audio project. This was the first clear way forward.

I’m glad, Jon, that you mentioned gaming as an inspiration. When technical people describe the differences between traditional multichannel and Atmos or the other newer immersive formats they will sometimes characterize the former as “speaker-based” and the latter as “object based.” But some immersive audio engineers I’ve spoken with feel this distinction is more relevant to games and movies than to music, where the height channels often serve as virtual loudspeakers. Do you guys ever do “steering” of mono images derived from the master tape when creating your Atmos mixes?

DF: Absolutely. We used the same captures that we utilized while making the 5.1, which we’d done in high-resolution back in 2003. We’ve created moments inside of each song where individual elements can be coming from above you or exclusively from behind because that tells the story better. Being able to take advantage of a fully immersive sphere of sound is even better than 5.1—object-based is a lot more fun.

JF: From a technical perspective, because they were engineered in stereo, a lot of our rhythm section tracks—the core of the song—have to be bussed, or “smashed” together in a very specific way. If you play those tracks—the kick drum, the snare, the bass—they don’t sound like “the song” and that’s because they’ve been smashed. There are limitations to how much we can split them apart into objects. Sound effects and reverb throws—things like that can go to the height channels [as objects.] I try to use them as sparingly as possible.

Sometimes, it seemed as if there was too much information even for 5.1. The additional channels definitely have a clarifying effect, allowing the listener to appreciate more layers of detail.

DF: I agree. We can keep groups of instruments that need to be together and interact with each other but we can also pull them apart where appropriate so you can hear and feel different textures in a way that wasn’t possible before.

I was happy the music videos were included because it reminds you that these are not just assemblages of sounds but songs that can be played live with guitars, bass, and drums. You can take it apart and reassemble it as something completely different.

DF: I was very pleased that when Wayne finally got around to putting the final touches on the Atmos version, he was grinning from ear to ear, like “I can’t believe this, how all this stuff is coming together—this is fantastic.”

There are plenty of correspondences between the 5.1 and Atmos mixes. Did you use the 5.1 as a starting point or did you start fresh from the multitrack master?

DF: When we sat down with Elliot back then [in 2003] we had very strong feelings about what was the best way to portray the emotional content of the material, and we didn’t throw the baby out with the bathwater. We repurposed a lot of those ideas because we still felt that they were effective. There were things we loved and we made sure to repeat them as part of the new Atmos release.

JF: We were strictly listening to the 5.1. We had no materials because that mix was all done on a digital console with a surround panner. So [the new Atmos mix] was [created] fully by ear. It was “listen and do it again” to recreate all those moments.

DF: It took a minute. [Both laugh.]

I feel that the decisions you made were quite successful. To name one example, in “Fight Song,” you have that shimmering guitar appear in the front height channels. It teases that effect out from what’s happening at ground level and it registers in a completely different way. There are a lot of examples like that.

DF: That’s the idea.

Here’s something that’s completely subjective, and I may be completely off base. To me, it seems like the mix becomes more immersive as the album progresses. It becomes a journey of sorts. Is there anything to that?

DF: Nothing intentional. I think it’s more the nature of the material and what makes sense on a song-by-song basis.

JF: “In the Morning of the Magicians” is sort of a peak. We’re putting the whole song in the rear left channel…

DF: That’s taken directly from the 5.1. It was undeniably effective in that format and there was no reason not to replicate it. We used to say [with the 2003 multichannel mix] that because there were five main speakers, we would create “star patterns” for things leaping around. “One More Robot,” for example. The bass would jump around in a star pattern—every note had a different speaker. With Atmos, we used a six-speaker pattern. We went left, right, then left surround, right surround. Then right rear surround, then left rear surround. So: front to back, left to right, then back to front, left to right. We kept ideas like that, reconceiving of them for Atmos.

When people have experience with Atmos—when they have any experience at all—it’s usually with the highly compressed version offered on one of the streaming services. Do you have any input regarding how your mix will be made available, other than on Blu-ray?

DF: I don’t think we have the ability to control that narrative but I feel pretty comfortable speaking for Wayne, and for the two of us, that it would be fantastic if we could get higher resolution streaming. I know it’s possible, it’s just not currently happening. An MKV release (MKV is a file format that can store different types of video and audio in a single file) would be fantastic, too, especially because, with that format, we could even include the videos.

JF: It would be great if there were an easier way to create MKVs and listen to them.

DF: Yes.

JF: That’s the best part of the Blu-ray. It’s just too hard to figure out how to listen to the MKV. It’s still an emerging format.

_______________

The Warner/Rhino Blu-ray dropped on November 1st; streamed Atmos versions have been available for some time. In the physical disc’s liner notes, Jon Fridmann cautions about the sonic limitations of streamed Atmos in its current state, and his advice certainly applies to the Yoshimi I streamed from Apple TV+. Compared to the Dolby TrueHD sound of the Blu-ray, the Dolby Digital Plus of the streamed album is coarse and fatiguing. Images were stuck to the front of each speaker, without the room-filling dimensionality heard from the Blu-ray. There was a considerably lower level of musical detail and less rich characterizations of vocal and instrumental signatures. One can hope for a downloadable TrueHD MKV file in the near future, but that seems like a long shot. Do yourself a favor. If you’re set up for Atmos, get the Blu-ray and experience a true immersive masterpiece.

By Andrew Quint

More articles from this editorRead Next From Blog

See all

The Physics of Describing Music Reproduction

- Jun 10, 2025

Detailed Frequency Ranges of Instruments and Vocals

- Jun 05, 2025

Measuring the Relative Cost of Audio Experiences

- Jun 03, 2025